From Pella archives, this photo shows the land prior to any construction.

As a valued member of the Central College family, you may remember some of the significant moments in the history of the college. Central University of Iowa was founded in 1853 by the Baptist Church with much support from the community and Dominie Henry Peter Scholte, founder of Pella, Iowa.

Three different fires burned down many original Central University of Iowa buildings, destroying some of the history of Central’s early years.

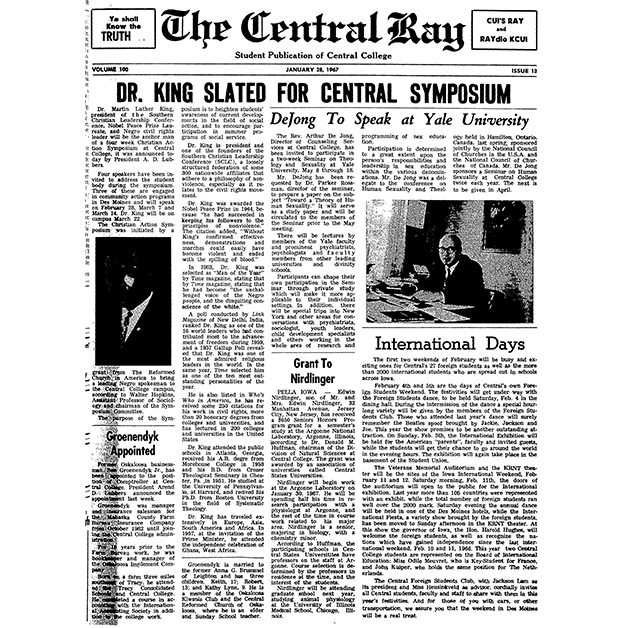

You likely have heard about the infamous Styx concert in 1975 that blew out the windows of Douwstra Auditorium. You may have attended or have seen photos of Martin Luther King Jr.’s visit to campus in 1968. But Central’s grounds have many untold stories that have shaped and supported the open-arm culture that has sustained Central for more than 170 years.

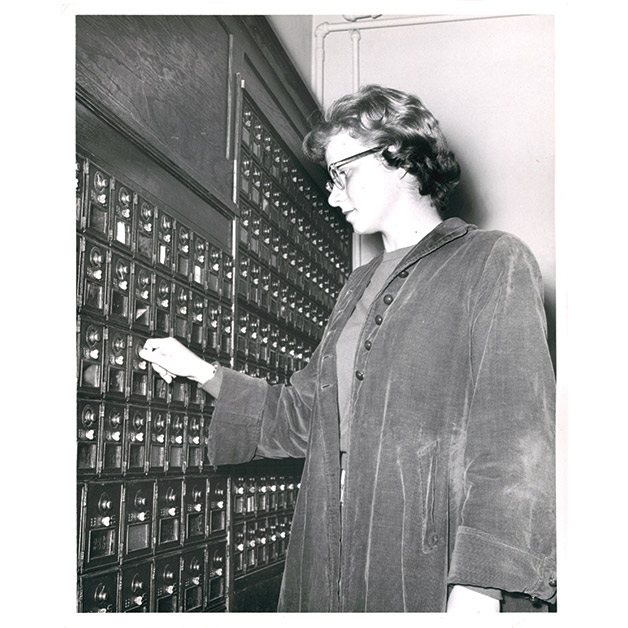

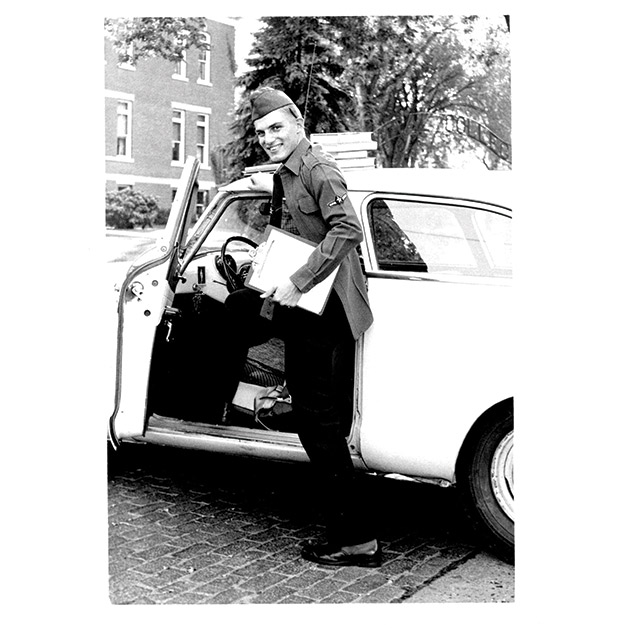

Some elements of college never change. Getting mail from home is always a highlight.

The Early Years

The Articles of Incorporation were adopted June 3, 1853. The essence of Central, whether guided by the Baptists of Iowa or Reformed Church in America, was to offer “equal advantages to all students having the requisite literary and moral qualifications, irrespective of denomination or religious profession.”

Central has been committed to offering a quality education at an affordable rate since its beginning. The Aug. 30, 1855, Pella Gazette published an announcement from Emmanuel H. Scarff, principal, “Tuition was published as $2.50 per quarter for common English branches, $4 for advanced English and higher mathematics and $5 for ancient languages. A convenient boarding house has been secured and arrangements have been made to accommodate a large number of students.”

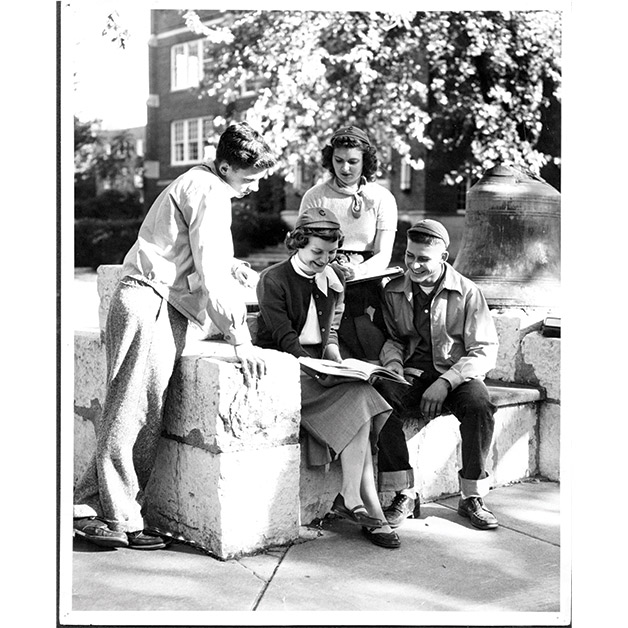

The Victory Bell was a backdrop to many Central student gatherings.

The first academic classes began in October 1854 under the principalship of Scarff. That same year the foundation for the first college building was set. The board decided to begin academic work without waiting for the new building. The first classes were in a two-story brick building on Washington Street, approximately four blocks west of the public square.

“The enrollment on the first day was 37, with quite a few from out of town, nine American families, several from Pella and the Holland families the rest,” wrote Scarff in his “Reminiscences,” which documented the first years of Central. “This small beginning increased almost daily, until at the close of the term our enrollment had attained to 73.”

The Central Academy served the role of college prep for the new community of Pella. The first courses were English, math and art. Within a few years the courses of study were divided into two levels — academic and collegiate. In the academic department, work included classical courses and was designed to fit the student for the higher walks of society and professional life. Collegiate students were given a hasty preparation for the immediate practical duties of life such as bookkeeping and teaching.

The first president, Rev. Elihu Gunn was inaugurated in 1857. In the fall of 1858, the college had enrolled 121 students per semester, yet only a handful enrolled in the collegiate classes.

According to the writing of K.K. Beard in “History of the First Twenty-five Years,” in the Alumni Record, the first class of graduates in 1861 from Central were Herman F. Bousquet, J.A.P. Hampson, Alonzo F. Keables, the Honorable W. J. Curtis, the Honorable Warren Olney and H. Kellenbarger. Despite challenging financial times, the school grew in favor and numbers, attaining a degree of prosperity as the fiscal year began in June 1857.

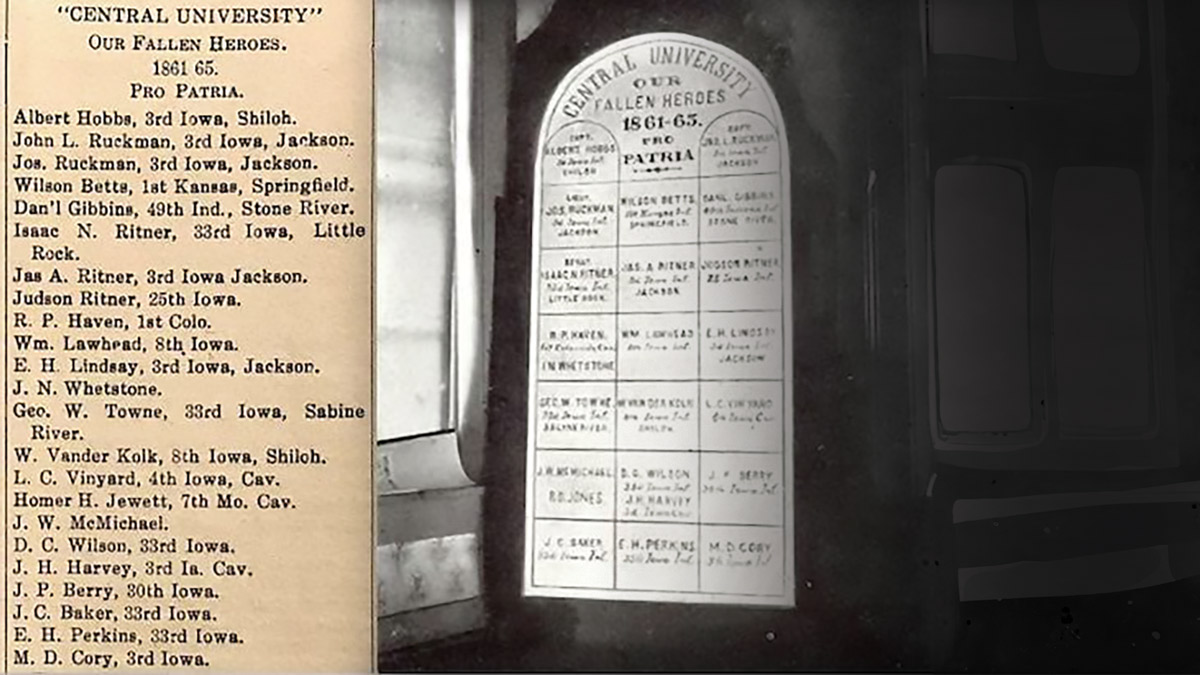

Generations of Central alumni may remember this memorial positioned in the back of the old chapel with the names of 21 Central students who died in the Civil War. The first was Albert Hobbs, Class of 1862.

As the U.S. entered the Civil War, enrollment dropped and 120 men and professors enlisted in the army. By the end of the war, 23 who fought in the Civil War died.

Mary Ver Meer Borg ’67 and her sister, Andrea Ver Meer Balmer, took a personal interest in the Pella and Central College Civil War history. They wrote a play, “Pella and Central College During the Civil War Years.” Borg used the archives from Geisler Library at Central and the Pella Historical Society to create a brief glimpse into the fledgling institution, students and Pella. Borg is the great, great-granddaughter of Tina Ver Meer, who Borg portrays in the play. Ver Meer was one of the early settlers who came to Pella in 1857.

In Pella’s Central Park stands a white obelisk honoring Captain Albert Hobbs, Class of 1862, a Civil War Monument dedicated by the Grand Army of the Republic (similar to today’s American Legion posts). Pella’s GAR Post 404 was named after Hobbs, the first local soldier and Central student to give his life in the Civil War. Other notable Civil War soldiers were Virgil and Newton Earp, Wyatt’s brothers, both Central students in 1861, who joined the Union and fought in the Civil War.

Professor Ellen E. Mitchell, who taught at Central before the Civil War, served as a volunteer nurse for the Union during the war. She resigned her professorship at Central and after the war became a practicing physician in India.

Generations of Central alumni have read the names of the lost soldiers on a marble plaque that hung in the back of the chapel for decades — a reminder of the cost of freedom.

The years following the Civil War are noted as dark and difficult for Central, yet it began to assume antebellum prosperity. Enrollment in 1865-66 was 313, according to Josephine Thostenson, author of “One Hundred Years of Service.”

The 1874 Catalogue of the Officers and Students publication (now called the Course Catalog) stated: “Pella, the seat of the University is situated 40 miles southeast of Des Moines on the Keokuk and Des Moines Railway and is of easy access from all parts of the state. It is a small city of about 3,000 inhabitants, standing on a gentle rise of ground, in one of the most beautiful prairie sections of the State.”

This same catalog also announced, “an endowment of $50,000 has been completed … a large portion of this sum has been contributed by old students and former friends and patrons of the intuition.”

Just 150 years later, Central still looks to its alumni and friends to sustain its future.

The first edition of the student newspaper, the Central Ray (aka The Ray, Ray, Central College Ray) was published in December 1876.

In 1967, Central announced Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., would be speaking on campus during the Christian Action Symposium. That spring, King inspired hundreds on campus with his message of equality and hope.

The financial crisis of 1877-79 caused hardship for most Iowans and Central almost didn’t continue. The newly appointed college president, L.A. Dunn, saw his supposed fortune passing forever away from his grasp. He was bankrupt, along with men all over Iowa. The tuition of students was bartered, mostly in the form of produce and food. Scarff wrote, “we all had enough to eat and wear but money was almost out of the question.”

By 1890, things drastically changed. Cotton Hall, a dormitory for young ladies, opened and included 22 rooms, a dining room and kitchen. It was described as “commodious with furnace heat and electric lights.” The Auditorium Building, later called the YMCA building, was also erected with a chapel, library, gymnasium, auditorium and several classrooms.

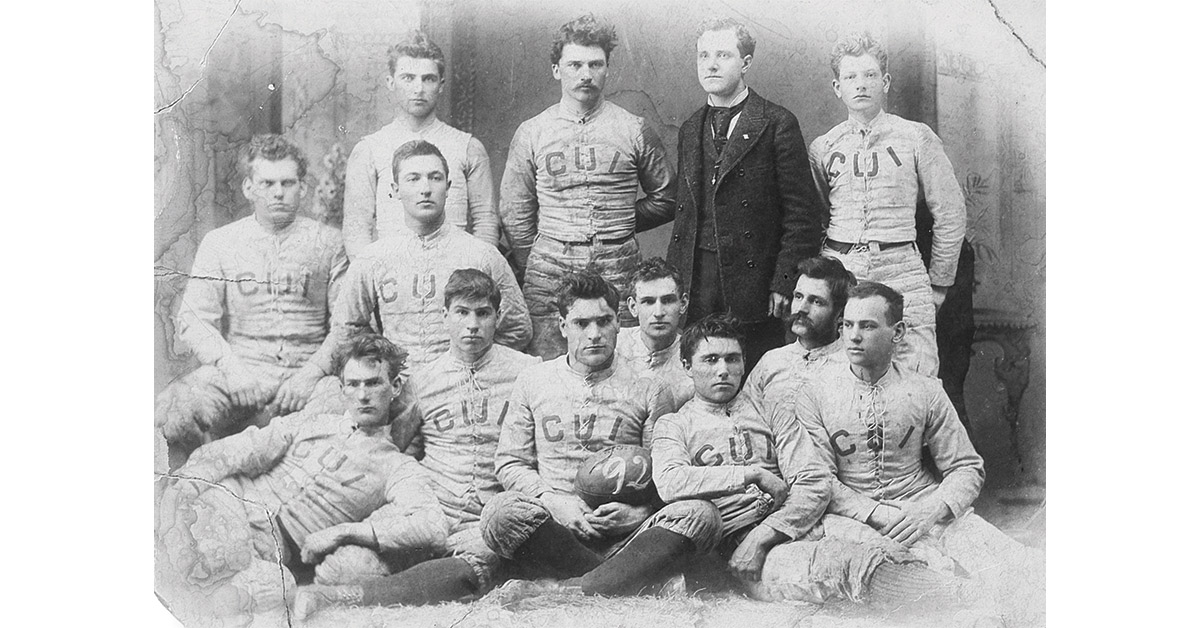

Central’s long legacy of love for football began in 1892 with the first-ever and only game of the year. The Central team lost to William Penn, 0-14.

From the 1870s to the end of the 19th century, the Baptist Church leaders confronted the question of keeping Central open. Should it be reduced to an academy? Should they merge with another college in Des Moines?

The Central football tradition began in 1892. Shown is the very first CUI football team.

Central’s music program tradition also enjoys a strong tradition. The Glee Club was mentioned as early as 1898 as “having an excellent program.”

A New Century

As written in the April 30, 1953, Pella Chronicle article by Thostenson, “As Central College entered the 20th Century, she had as her guide and administrator one of her own alumni, Reverend L.A. Garrison, Class of 1896. Garrison rallied the community and secured funding of $22,000. Robert Beard, Central board member, of Pella, offered his entire observatory to the college, including telescope, transit, spectroscope and clock, worth $4,000. Construction on campus moved forward with Jordan Hall in 1905.”

Long before the BEAKES, Central contended with the follies of Clark’s Happy Hobos, known in 1903 for fraternity pranks on students and faculty.

In 1904 a Central Ladies Auxiliary was created, and its first president was Harriet Keables. Its function was to raise funds for the college. Improvements included the renovation of Cotton Hall, refurbishing Old Central and Jordan halls and construction of a tool house and water tower. Funding raised also furnished cases for the magnificent Randolph collection, provided the science department with microscopic lenses and other apparatus, installed pianos for music studies and established the Stoddard Memorial fund to purchase library books.

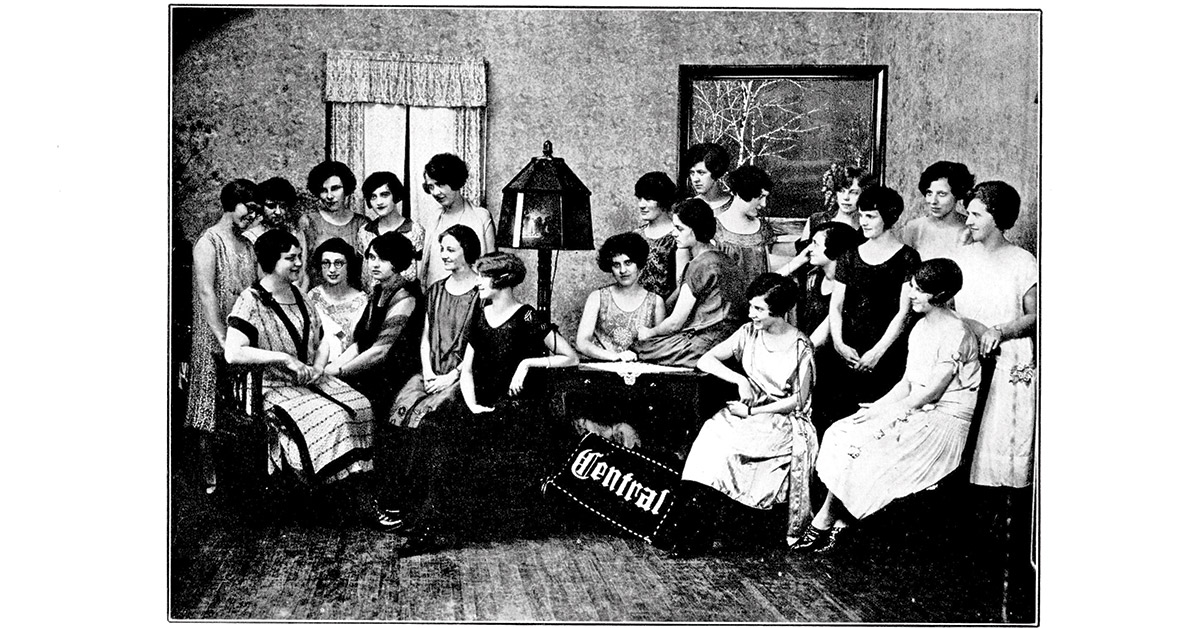

Women have always been accepted at Central College and women’s clubs helped them flourish — this photo is from an 1890s women’s club gathering.

The CUI Fight Song was created in 1906 when Garrison, president of Central, offered a prize to the writer of the song that would become the Central school song. The original melody was composed by Winnie Zitterell Rhodes, Class of 1907, and the words were written by George Cavanaugh, Central’s first athletics coach. He wrote a second verse that has been dropped. Pianist Guy Churchill created an accompaniment, and it was sung by the men’s Glee Club.

The inaugural edition of the “Central College Pelican” was published in May 1907, and continued to be published annually except during WWII, until 2008.

1907 also welcomed the first ladies’ basketball team. Night school for “Normal and Commercial Department,” the predecessor to business school, opened in 1907, offering courses for working adults.

The strong music reputation at Central began in the early years. The Glee Club made its first tour outside of Pella in March of 1907 and another tour in 1909 over five weeks to western United States.

Many readers may know that in 1916-17, CUI transferred from the Baptists of Iowa to the Reformed Church in America. The Baptists of Iowa wanted to consolidate their colleges and selected the Des Moines College, which closed in 1930. After 63 years under the Baptists of Iowa, Central came under the guidance of the Reformed Church in America. These were challenging times for President William Bailey to ensure alumni of “Old Central” always were part of and welcomed.

Students take the time-honored passage under the Central College

arbor to campus.

World War I

The next 10 years Central experienced fires, the entry by the United States into World War I, construction of Graham Hall, Ludwig Library and a combined gymnasium and chapel.

Bruce Boertje ’79, Pella Preservation Trust member and history enthusiast for Pella, has completed significant research into the Central and Pella history and shared information. One of Boertje’s favorite historical moments reflects Central’s patriotic duty for WWI.

When the United States declared war on Germany, Central sent many of her sons into the service of her country and offered her equipment to the government for the establishment of a unit of the Student Army Training Corps. After the new women’s dormitory, Graham Hall, was opened, Cotton Hall was transformed into barracks for the S.A.T.C. until the armistice of WWI was signed.

Then the same day that the S.A.T.C. students moved out, the building was converted into Pella’s first hospital during the influenza pandemic of 1917-19.

Pella honored its first casualty of the World War by naming the legion post the Van Veen – Van Hemert American Legion Post. Gerrit Van Hemert, Class of 1919, and John Van Veen were the first Pella men killed in action.

In 1917, Beard Observatory was installed above the trees on top of Ludwig Library. “It’s six-and-one-half-inch lens is one of the largest in the state and gives fine facility for the study of astronomy,” according to the 1917-18 Central Catalog.

The YMCA building burned in 1917. Another fire destroyed “Old Central” Hall on June 14, 1922. The loss of pianos, office supplies and furniture, though significant, was not the most severe loss. Many sentiments were attached to Old Central as the first building erected on the college campus. Ground broke for the “new” Central Hall in 1928. Cotton Hall suffered fire damage in 1923.

The C Club for athletes was created in the fall of 1923.

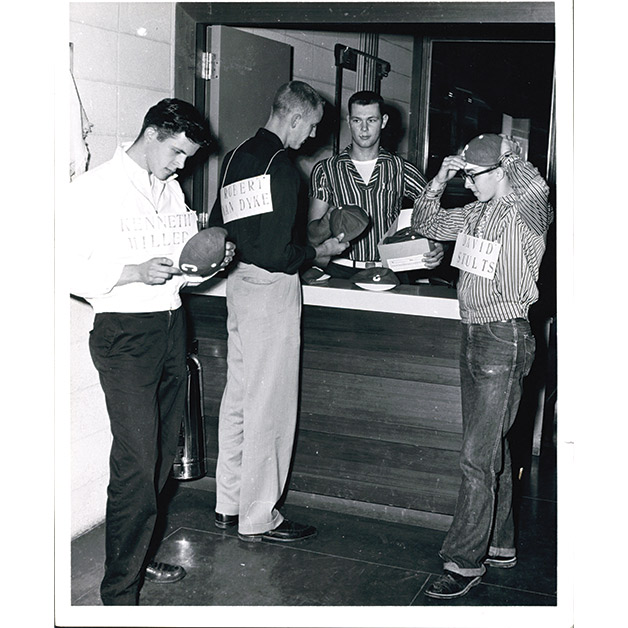

Central’s first-year student tradition of making the “frosh” wear green “togs” beanie hats and ribbons began in 1925. The Student Council published the edict for “first years” about when and where they must wear their hat and ribbons, in the Oct. 10, 1925, edition of the Central Ray. If caught without the beanie, the student would be tasked with chores like carrying an older student’s books. The “Freshmen Daze” tradition continued until 1971.

The infamous green beanies were given to all first-years to wear the first months of college.

The fall festivities around football instigated the first Central Homecoming on Nov. 11, 1928. Snowflakes fell but that didn’t keep anyone away. Though the final score was Western Union 7, Central 6. The “Pelican” reported it was a well-played game. At this point in time, Central’s football field was just west of Central Hall.

The Central Academy was discontinued in 1928 because the local high schools were providing the necessary requirements for college applications. By 1929, Central’s endowment had reached $200,000 but the college needed $300,000.

The Class of 1930 has the distinction of being the first class to not have a public commencement exercise due to the smallpox quarantine. This class and the Class of 1929 left a reminder of their time by presenting the “Victory Bell” and the 40 ft. steel tower.

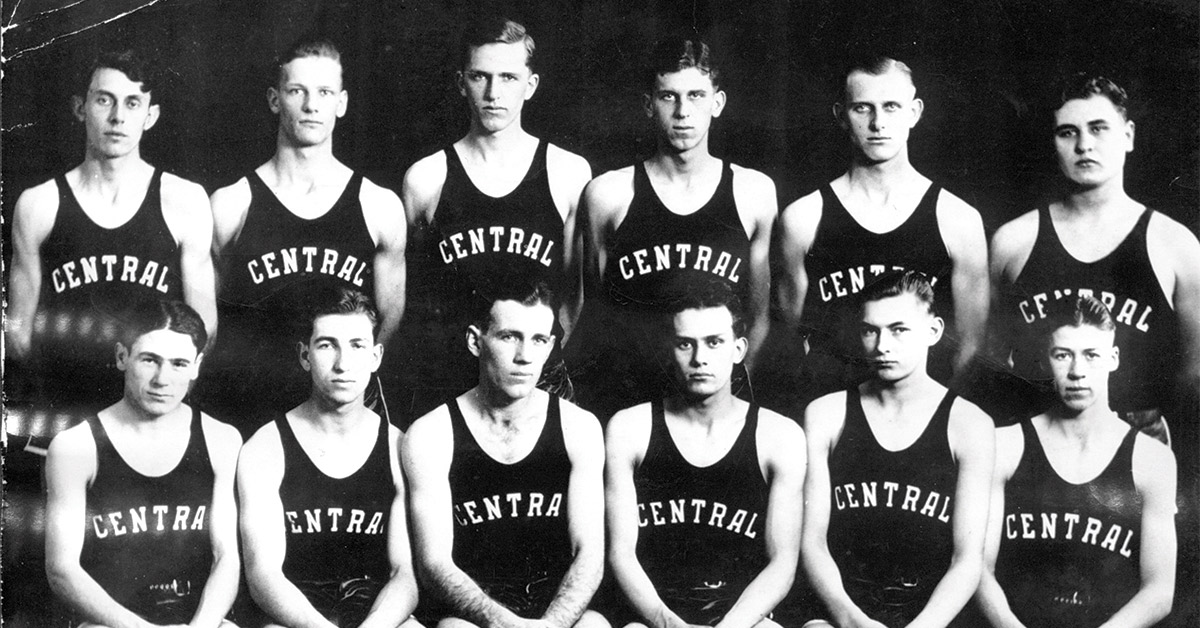

The 1930s Central basketball team was called the wonder team and gained the namesake, “Cradle of basketball in Iowa.”

The Depression tightened its grip on Central by 1933. Administration did all within its power to aid students to continue to secure an education at a minimum of expense. The faculty and the college accepted locally grown produce and services from students as a form of payment. Potatoes, carrots, cabbage, eggs and milk were also accepted from students determined to get an education.

Enrollment during these challenging times fluctuated wildly. In 1917-18, enrollment dropped to 50. In 1926-27, it climbed to 200, falling to 100 during the 1928-29 academic year and rising again to 265 in 1936-37.

Much of the growth can be attributed to the “earn-your-way program.” The Student Industries program started by manufacturing an educational toy from scrap lumber and bore the trade name, Bildertoy. The Student Industries expanded in five years to include manufacturing storm windows, ironing boards, folding tables, spark arrestors, window screens, hog feeders and other millwork and cabinet making. It also helped with the sale and distribution of tulip bulbs.

In 1938, the campus footprint expanded from the railroad tracks to West Third Street, thanks to a gift from Peter H. Kuyper in memory of his father A.N. Kuyper. This allowed for the second football field to be developed on campus and named in memory of A.N. Kuyper, in the space south of where Geisler Library stands now.

During the 86th Commencement, the concept of building a new chapel became a reality. Many gifts were received, and the most substantial gift came from Rev. Richard D., Class of 1901, and Mrs. Lena Bramm Douwstra, Class of 1902. Douwstra Chapel was dedicated in 1940.

During World War II, Central students, like the rest of America, were eager to serve their country. And after the war, the GI bill brought many back to campus for an excellent Central education.

World War II

The second world war hit the campus hard. The most significant contribution to WWII was the personnel. Estimates have more than 600 Central students and alumni participating in one of the service branches and in almost every rank. The Pella Chronicle reported that 21 young men lost their lives in the war.

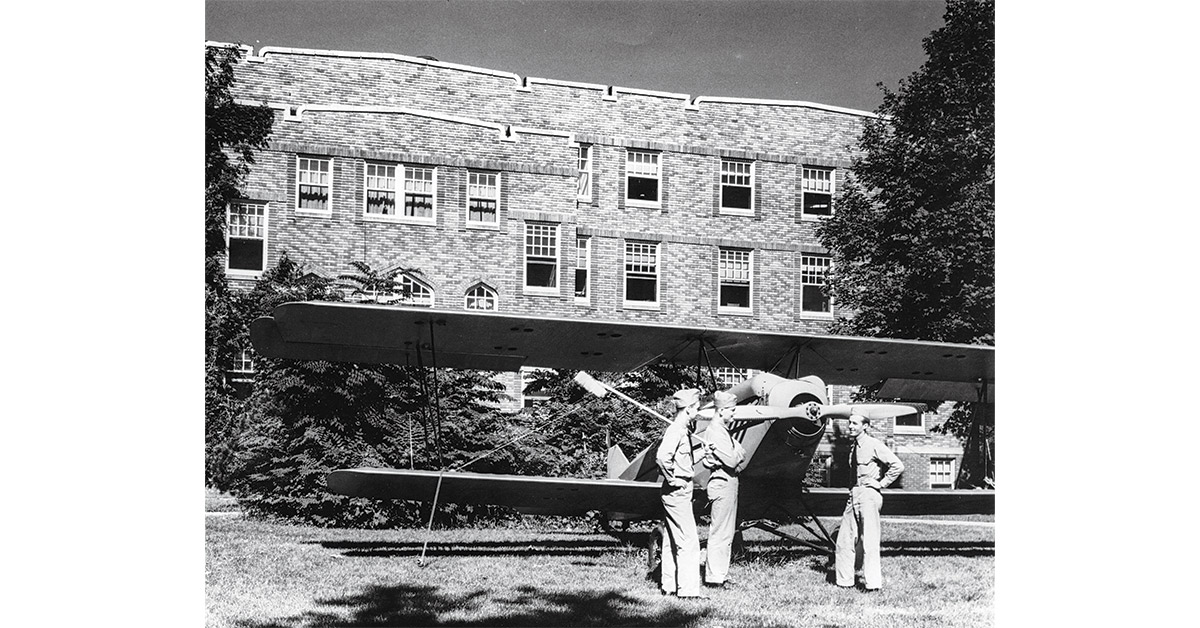

One very notable impact of the war on campus was the pilot training school in 1942. “As part of the federal government’s Civilian Pilot Training program — later called the War Training Service — Central offered four, eight-week courses of 240 hours of study each. Students were paid a stipend of $100 per month — ‘scant enough to keep one in board and room and shoe polish,’” according to a Sept. 4, 1942, article in The Central Ray. Read more on the school in Civitas, “A Pivot to Pilots,” Nov. 13, 2020.

The pilot training program literally took over Graham Hall, transforming it from a women’s residence hall to barracks.

Despite the wars in Europe and the South Pacific, Central welcomed Princess Juliana of the Netherlands in 1942. Her party included Alexander Louden, the Netherland’s ambassador to the United States, who delivered the 1942 Commencement address. Princess Juliana was awarded an honorary Doctor of Law degree.

As part of the National Student Relocation Council’s efforts, Central brought 10-12 Japanese American students to the camp from the internment camps in the western U.S., explains Lois De Haan Smith ’68, associate professor emerita of library science. The Reformed Church supported this effort and several of the students lived with local families.

Ahead of its time for the 1940s, Central had a no-smoking policy for decades. On Oct. 16, 1946, Ralph Hays ’47, president of Student Senate, submitted a reminder in the Central Ray to students: “Your enrollment at Central entails keeping the rules. The Central College catalogue reads, ‘The college deprecates for hygienic and economic reasons, the use of tobacco by persons of college age and requires the students abstain from its use in all college buildings and on college grounds.”

The Kuyper family continued to support athletics with the development of a stadium in 1949, replacing the project started in 1938. The stadium would be redeveloped again in 2007.

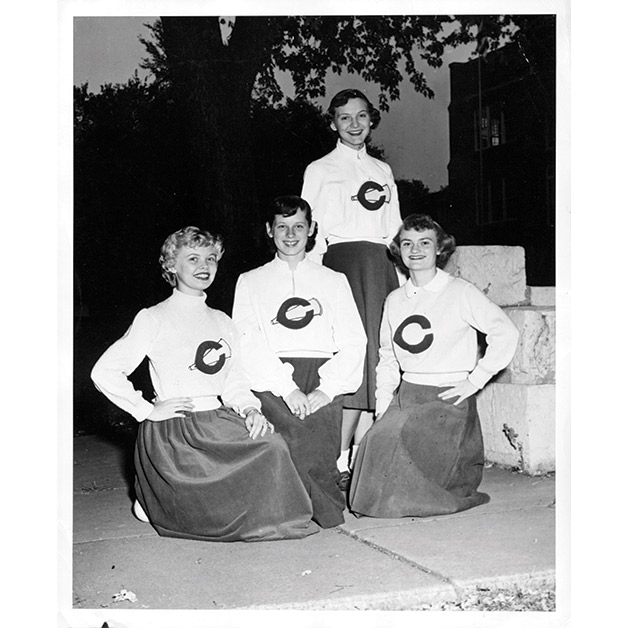

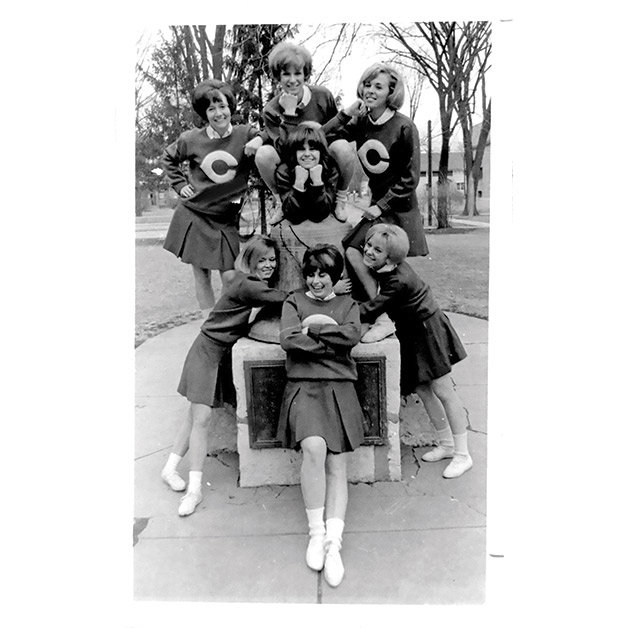

1940s cheerleaders could be credited with setting the groundwork for recent national champion cheer and dance teams.

The 1950s On

Following WWII and the Korean War, the G.I. Bill enabled a large influx of students on campus. This era is filled with growth in buildings, housing and academic programs. In 1952 the R.R. Beard telescope was moved above the bleachers of Kuyper Field. In 1954 the Student Memorial Union was constructed, and the dining hall opened in the new wing of Graham Hall.

As early as Fall 1949, a student-operated radio station filled the airways of Pella. The first was KEBS, Marvin Lee ’52, then a first-year student, was credited with originating the idea. The AM station closed in Fall 1957. After working on a new FM radio station since 1959, the new student-run KCUI radio went on the air Feb. 27, 1961. The station began broadcasting 15 hours per week. It expanded over the years to 24 hours.

These ladies helped bring the cheer to Central college games.

In an article published in the Central Ray, the Henry W. Pietenpol dormitory was dedicated Oct. 21, 1962. The French House opened followed by a wave of language houses.

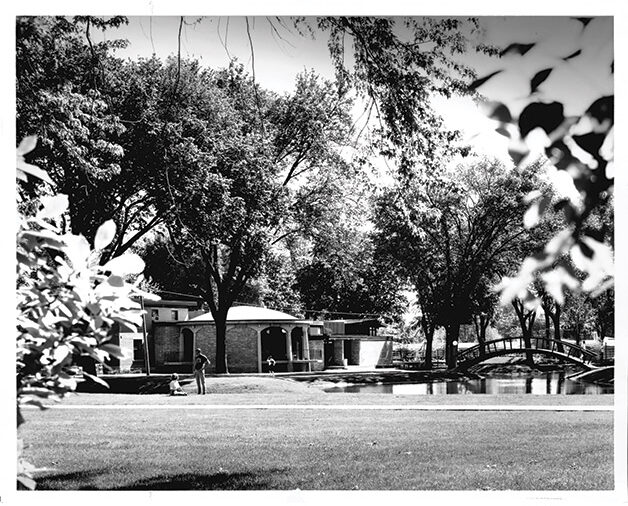

Peace Street was closed in 1964 and Lake Lubbers, nicknamed “Lubbers Lagoon,” was created. It became part of the annual Homecoming Lemming Race in 1977. According to a 1992 Central Ray article, the bridge originally was built with a high arch to accommodate ice skaters and to replicate authentic Dutch style. It was a hazard. Over the years, it was made of wood with steps, railings were added and is now smooth concrete for safety and accessibility.

The bridge over the pond was a focal point on campus beginning in the 1970s.

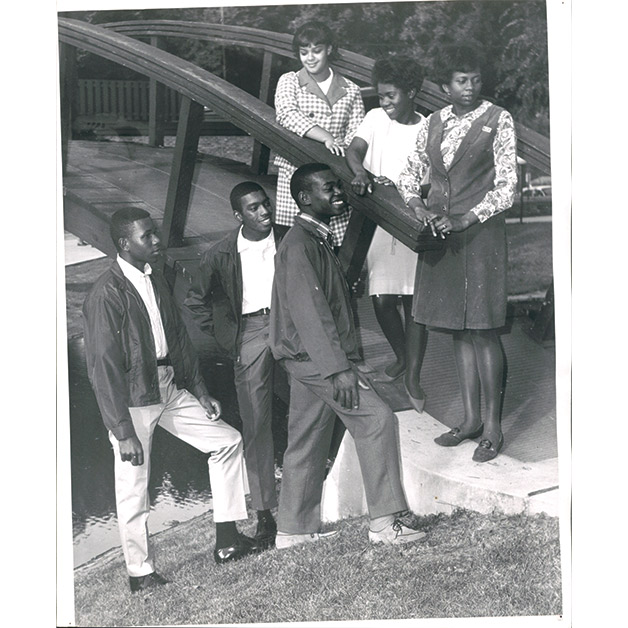

Housing and organizations on campus developed in the 1970s when Central had 100 Black students. Central had an Afro house and Afro-American Organization in 1972. The United Black Association began in 1977 and evolved into the Coalition for a Multi-Cultural Campus in 1989. Today campus welcomes The Black African American Student Union along with six other organizations that promote diversity and inclusion.

In 1974, the college opened the Geisler Learning Resource Center (Geisler Library). It also housed the education department. The Brower Collection was housed here, including the masterpiece “The Holy Family,” attributed to Peter Paul Rubens. It was displayed in a special archive room that contained the rare books.

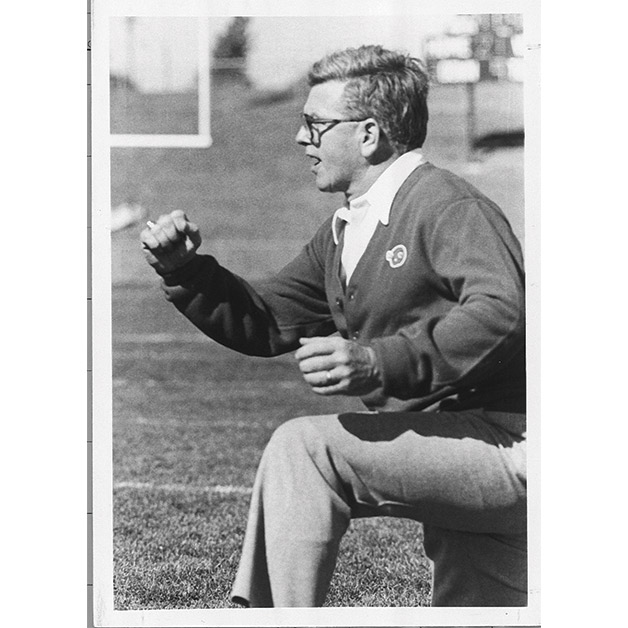

Central’s football team won the national championship in 1974 under Coach Ron Schipper. The football stadium had moved to its current location, now called the Ron and Joyce Schipper Stadium. It underwent reconstruction in 2007.

Football Coach Ron Schipper loved the game. He led the Dutch to win 18 Iowa Conference championships and the 1974 NCAA Division III national championship.

The “old” library building became the Lubbers Center for the Arts, housing the art department with space for ceramics, sculpting as well as a new kiln. The radio station KCUI-FM made its home on the mezzanine. Libraries on campus had been in Old Central (destroyed in 1922), YMCA/Auditorium Building (destroyed in 1917) Ludwig Memorial Library (opened in 1920) and the Geisler Library (opened in 1974).

The Kenneth Weller administration is credited with the largest amount of facility construction and renovation of all Central presidents. He came to Central in 1969 and retired in 1990. He is credited with constructing the Geisler Learning Resource Center, Vermeer Science Center, A.N. Kuyper Athletics Complex, Kruidenier Center for Communication and Theatre, Chapel, H.S. Kuyper Fieldhouse and the Maytag Student Center. An Oct. 27, 1989, article in the Chronicle indicates 95% of the college’s classroom space had been rebuilt or remodeled since his arrival in 1969.

Central campus heralded the student union until 1989 — a landmark at Central.

Maytag Student Center centralized gatherings on campus. The movie theatre that had been in the Scholte study lounge, moved to the student center along with the bookstore and post office, which had been a small outbuilding until 1989.

The name change to Central College and sunsetting of CUIFS and CUI happened in 1992. However, the 1853 charter calls the institution “Central University of Iowa, commonly known as Central College,” from the beginning. Further justification for the name change was the fact that Central is not a university. The founders had envisioned a campus with different schools for law and medicine, which did not materialize.

The history of Central continues to be experienced and will be documented in new ways of archiving the memorable moments of students. The Ray, aka The Central Ray, ceased operation in 2008. The Pella Chronicle, aka The Chronicle, ceased publication in 2020. The annual yearbook, the “Pelican,” ended in 2008 after 101 years. The digital world will honor the history of the past and share memories yet to be lived.

For information on women of Central, Iowa State has a tribute to influential women of Iowa and includes a section on Central College: central.edu/plaza-heroines.

View past presidents of Central at central.edu/past-presidents.

Access digital archives at central.edu/digital-archives.

Sources: Interviews with Mary Ver Meer Borg ’57, Lois De Haan Smith ’68, Bruce Boertje ’79 and Valerie Van Kooten with research by Kyle Winward, Central technical services librarian.

To encourage serious, intellectual discourse on Civitas, please include your first and last name when commenting. Anonymous comments will be removed.

Comments are closed.