Kenneth Weller is remembered for his magnanimous vision, his strong leadership and his immeasurable kindness. His dedication to Central College and its students — shared here in his own words as well as through the memories of others — had a transformational effect at the college and created an unforgettable and enduring legacy. It’s safe to say, Weller accomplished what he set out to do.

The students’ anger burned with the intensity of the Yucatecan sun.

In 1975, the headquarters for Central College’s popular international study program in the Yucatán was moved from a convent in Mérida, Mexico, to a former governor’s mansion the school rented. President Ken Weller journeyed from Pella, Iowa, a few weeks later for a quick site visit. Approximately 20 students were spending the fall trimester there and Weller gathered them together to hear how they liked their elegant new surroundings.

Weller knew what student unrest looked like. He had an up-close view in his first year as president in 1969, as Vietnam War protests raged.

But he was caught off guard as his eyes scanned the room and were met with looks of irritation and impatience. Almost immediately, the meeting on the warm, muggy evening in Mérida took an ugly turn.

“The students complained bitterly — bitterly! — about the fact that there were no seats on the toilets,” recalls Professor Emeritus of English John Miller, who spent the term providing instruction in Mérida that fall. “It’s common in Mexico, even among the upper class like the governor, to just have porcelain on their toilets with no cover at all. But the students were not used to dealing with toilets in that way.”

And they wanted to know what their college president was going to do about it. “So he got on the public bus,” Miller says. “He took the bus to downtown Mérida, to the Sears store. He bought some toilet seats, carried them back on the bus and installed them in the house. Himself. He didn’t say, ‘John, go do that.’ Or he didn’t say to the students, ‘I’ll see if I can get that taken care of.’ He took the bus.

“That’s always been a memory for me. He really cared for students, and he really cared for faculty as well. And he just took things into his own hands and did it.”

Weller died March 18, 2022, at age 96, prompting a cascading stream of affection and sympathy from throughout the Central family and far beyond.

Retired college presidents, like old soldiers, typically fade away. But Weller, while carefully keeping his distance from any thorny issues his successors were dealing with, always remained as much a part of the fabric of Central as the A Capella Choir’s benediction and Lemming Day, growing more beloved with each passing year.

There were no doubt missteps and frustrations during Weller’s presidency but as alumni look back, they dim. They’re outshined by images of the era’s record-breaking enrollments and fundraising numbers. A near-total makeover of the campus with a 20-year flurry of construction and renovation projects, requiring not a penny of debt. The growth of innovative international study programs. Unprecedented athletics triumphs and championships, undergirded by pioneering roles in charting Division III’s course and providing competitive opportunities for women. The longest tenure of any Central president (1969-90), followed by an impactful 32- year post-presidency. Weller’s calm, steady voice was influential not only on the pristine Central campus, but in the Reformed Church in America, the NCAA and within higher education nationally.

His achievements were too plentiful to enumerate, yet for so many, the memories they cherish in misty-eyed conversations after he passed had little to do with what he accomplished, but how he made them feel.

“You Listened and You Gave Us a Voice”

Weller’s Mérida quest for toilet seats reflected more than his Dutch Calvinist belief in self-reliance. He possessed that rarest of gifts, not only the willingness to listen but an eagerness to do so. He spent much of his first year as Central’s president, not implementing a five-point plan, but roaming the campus and visiting individual offices — just to listen.

And that’s how he responded on a spring evening in that first year when a boisterous group of war protestors stormed to the front door of his on-campus home, chanting profane sentiments about the atrocities of Vietnam, while Weller’s frightened young son, Matt, hid under his bed.

“I finally identified a few voices in the crowd,” Weller said. “I approached them and said, ‘I’ll see you in my office at 10. We can talk about this intelligently.’”

And they did. Not long after that, Weller led a candlelight campus march from the student union to the Tulip Toren on the Pella town square.

“To give you an idea of how many people were there, the last person to leave the student union was still there when the first person reached the tulip tower, single file, carrying candles,” Weller said.

Trustee Emerita Sue Spaans Brandl ’65 of Pella noticed an immediate change.

“Students respected him after that,” she says.

The characteristic empathy Weller displayed to those students, feeling helpless about a war they thought must be stopped and hungering to be heard, was felt, sometimes years later.

“I’ve been told by the leaders from that day, ‘You listened to us,’” Weller said. “‘You didn’t agree always but you listened, and you gave us a voice.’”

“I did not have a grand and glorious plan for what I wanted the college to do. In my inaugural speech, I just said I’m here to help these students become what they wanted to become.”

— Kenneth Weller

It Was Providential, Perhaps

Looking back at his life’s path, Weller sensed that his course was directed and redirected by random circumstances.

“A whole lot of things came together — it was providential, perhaps, or just lucky — but I ended up with jobs that I never had an expectation of being involved in,” he said.

Indeed, it’s perhaps unlikely that one of America’s top 100 college presidents, according to a 1987 ranking, was the son of a Dutch immigrant who never attended high school. His mother, Gertrude, didn’t graduate, either, but placed high demands on her only child to perform academically while he grew up in Holland, Michigan. Weller recalled that his school’s athletics eligibility standards were not nearly as restrictive as Gertrude’s. His chemistry teacher had to call to assure her that Weller was keeping up in class before she would allow him to take the field for a football game with nearby Grand Haven.

After returning from service in World War II, then graduating from Hope College in 1948 and marrying Shirely in 1950, he received a grant for doctoral study in economics and business at the University of Michigan. Intent on a business career, Weller had little interest when Hope president Irwin Lubbers, a former Central president, asked him to consider teaching there.

Lubbers sweetened the offer.

“He said, ‘If you guarantee me you’ll teach a full load in business and economics, I’ll let you coach football,’” Weller shared.

“Bingo!” Weller said with a laugh.

Weller served as an assistant coach, famously including the years future Central football coaching icon Ron Schipper played quarterback for Hope.

But Weller discovered an even greater zest for the life of the mind, turning down the head football coaching position to remain a full-time faculty member. He was content in that role when Central trustee Paul Farver traveled to Holland, Michigan, to meet with Weller in 1969.

“He suggested what was to me a very foreign idea,” Weller said. But soon he and Shirely were packing a moving truck bound for Iowa to begin his presidency.

“In almost every one of these situations, becoming a faculty member and becoming a president, I felt somewhat inadequate,” Weller said. “I did not have a grand and glorious plan for what I wanted the college to do. In my inaugural speech, I just said I’m here to help these students become what they wanted to become.”

Former Central presidents David Roe (left) and President Emeritus Ken Weller (center) join current President Mark Putnam at the 2013 NCAA Division III softball championships in Eau Claire, Wisconsin.

1969

Trustee Emeritus Harold Kolenbrander ’60 of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, is familiar with the minefields that new college presidents must gingerly navigate.

A former chemistry professor who returned to Central to join Weller’s staff in 1975, he eventually served as the college’s provost, then was a widely admired president at what is now the University of Mount Union (Ohio). He said that 1969 was a treacherous time to launch a presidency.

“There were a goodly number of first-year presidents who started at that time who had one-year presidencies,” he says.

Miller, now living in Louisville, Kentucky, said the times were uncertain and so was Weller’s initial reception.

“I would say that Dr. Weller was thought of as being a promising president but the faculty didn’t embrace him until somewhat later,” he says. “That’s pretty common. He came from a business background and that was of some concern to the faculty, so he had to prove himself, but he did pretty soon.”

A Consensus Builder

Always, the first step for Weller was hearing what others had to say.

“I really felt his calling was to nurture the next generation,” Brandl says. “No one felt like he was going to come in and just shake up and change everything. It was, ‘No, I’m going to listen, I’m going to ponder it and I’m going to try to guide and enrich the lives around me.’ And that’s exactly what he did.”

Decisions were never impulsive.

“He was a huge consensus builder,” says Rev. Steve Mathonnet-Vander Well, a pastor at Pella’s Second Reformed Church where the Wellers worshiped. “He didn’t lead by standing on a soapbox and saying, ‘This is right.’ It was, ‘How can I find a way that most people are going to say this is a good decision?’ And consensus builds trust. You didn’t ever sort of wonder, where did that come from? It was always an idea that had been talked about to many people.”

While the process was deliberate, he didn’t dodge delicate issues. Board Chair Emeritus Lanny Little ’74 of Bonita Springs, Florida, was a student trustee at Central and later served on the board. He recalls Weller inviting Little and fellow student trustee Ted Grubb ’74 to his house to address a concern.

“It was a matter of trying to learn perspectives the students had through our eyes and our comments and then to open our eyes and our ears to perhaps a broader range of responses than what we maybe presumed would be there,” Little says. “And that was so much his leadership style. He just approached the issue and dealt with that in a very matter-of-fact and wise fashion, no matter how contentious the issue might be. That was always something that I appreciated about Ken.”

Weller quickly dialed down the temperature if discussions threatened to get heated but conversations with him almost never did.

“Ken would get frustrated, to be sure, but I think he probably handled it by going to play racquetball and windsurfing,” Kolenbrander says. “I had 11 wonderful years with Ken and I don’t remember once him losing it. I started scouring my brain and I can’t come up with an instance.”

Ardie Pals Sutphen ’64, of Pella, Iowa, served as Weller’s administrative assistant for the final five years of his presidency. She can’t even recall an angry phone call or letter that he received.

Students and faculty soon developed an unspoken trust in their president.

“When he put forth his ideas and then his decisions, you had a very, very high confidence that it was the right thing to do,” says Trustee Emeritus Ken Braskamp ’65 of Los Angeles, California.

That trust was earned.

“Pure honesty,” says retired Vice President for Development Gary Timmer ’55 of Pella. “He never faked anything.”

“It Felt Special”

What won over skeptical faculty members and students went beyond listening. Weller had a way of leaving visitors feeling like he saw the world through their eyes.

“I felt my success as a president, whatever it may have been, was largely determined by the fact that I felt like a faculty member who took on some additional administrative duties,” Weller said. “I never thought of myself as an administrator.”

Miller recalls leading a book discussion group at church. Weller was an eager and engaged student.

“I really appreciated that a lot, that he was interested in what I was interested in,” Miller says. “He did things with faculty. He and I played racquetball at the gym once a week for years and years. He had faculty over to his home. Even in the very first years he would invite small groups to his house.”

Eric Van Kley, director of athletics and head wrestling coach, smiles about the impression a visit with Weller created.

“He always left me feeling like wrestling was his favorite sport,” he says. “But if you talk to Jeff McMartin ’90 or George Wares ’76, they’d tell you, ‘Oh, no, football was really his favorite sport’ or ‘softball was his real favorite.’ He made you feel like you were one of the most important people in his life.”

Conversations with any visitor were as comfortable as old jeans. A job title or social standing were insignificant.

“He came from a family background where they were very concerned about the individual no matter what their status, whether they were a laborer or an executive,” Braskamp says. “They were all the same to him. And so he had a great passion for making sure everybody felt good about who they were.” That style resonated with Trustee Emeritus Mike Orr ’69 of Monona, Wisconsin. “He was always interested in me as a person, not as a faculty member or a board member, but truly interested in me,” he says.

The first campus job for Little as a first-year student from Phoenix, Arizona, was to help take care of the president’s house. It morphed into a regular social engagement as well.

“Any time I was there to work, if Ken was there, there was always time to sit down at the end and just get to know each other,” Little says.

And he was visible. Most students in the ’70s and ’80s have memories of seeing Weller visiting with a student in front of Central Hall, climbing the steps of the wooden campus bridge, carrying his lunch tray to one of the round tables in Graham Dining Hall or riding his motorcycle to a softball game, necktie flapping in the breeze.

He could find time to roam campus because his workday routinely started at 4:30 a.m.

“No one ever worked harder as president,” Timmer says. “I don’t think they could have. No one else got up that early.”

Former trustee Emmit George ’72 of Lisle, Illinois, was a basketball player at Central. He also served as student senate president as a junior and grew increasingly involved with the campus organization for African American students. The ensuing time-commitment crunch caused him to give up basketball his senior year. That meant surrendering the small scholarship he received in the days prior to NCAA Division III competition. Weller made it possible for him to retain his scholarship to complete his education.

George never forgot that. But even more he recalls being invited to Weller’s home, getting to know his family and playing racquetball with him once a month — and always losing.

“I didn’t realize the significance of the access that I had as a student with the college president until later,” he says. “I certainly appreciated it. His door was always open.”

That mirrored the experience of former softball catcher Laura Bach Olson ’93 of Mapleton, Minnesota.

“You knew you were important to him,” she says. “I don’t know how many people would think that if they were having a rough time or they needed something that you could walk into the president of the university’s office and talk with them. We went to his house right away when we were freshmen and he knew who I was. It felt special.”

It was a trait that was never diminished by age — the way his aching knees and hearing were. That touched Mathonnet-Vander Well, who says pastoral visits to senior care centers can be sobering as residents deal with quality-of-life issues.

“But when you left the Wellers you were always built up, stronger, more committed, felt affirmed and encouraged,” he says. “Not that everything they said to you was just, ‘It’s wonderful,’ but they gave you wisdom. They gave you honesty. They gave you energy.”

The infamous Weller peanut butter knife at Pella’s Second Reformed Church is continued evidence of Ken Weller’s caring commitment and fix-it leadership style.

Deeds Over Creeds

Shortly after Mathonnet-Vander Well and his wife, Sophie, arrived as co-pastors in Pella, they had their first encounter with the Wellers.

“This young mothers’ group is meeting and we’re looking around and who’s in the nursery taking care of the young mothers’ kids but Ken and Shirely Weller,” he says. “It’s just not where you expect to stumble upon a college president. I mean, you expect a phone call that, ‘I’d like to meet with you, can you be at my place.’ Instead, where should Ken and Shirely be but holding slobbery babies in the nursery. And he was so very comfortable with it. In fact, he enjoyed tangible expressions of faith and commitment.”

The Wellers were also an integral part of a church crew that prepared free lunches for children during the summer. Of course, being the leader he was, Weller found ways to tweak the process.

“We still have the Weller peanut butter knife (in the church kitchen) because he was the peanut butter guy,” Mathonnet-Vander Well says. “He thought the knives we had were not very efficient, so he went out and got a special knife to smear the peanut butter on.”

As much as serving, Weller relished getting to draw closer to the other volunteers.

“Deeds over creeds was one of his favorite lines,” Mathonnet-Vander Well says. “What builds community? Giving out lunches to children, that builds community rather than sitting here debating about Jesus’ miracles.”

Teammates

Weller’s partnership with his wife Shirely was essential to his presidency. Raised during hard times in the Depression, Shirely is plain-spoken and honest. She has an ability to cut to the heart of an issue in an endearing manner.

“They were a great team,” Miller says. “And the faculty loved Shirely. They had a very high regard for her.”

With each promotion and honor Weller received, she ensured he retained his trademark humility.

“If that education balloon or athletics balloon flew off too high, it was Shirely who brought it back down,” Brandl says. “She grounded him so much.”

Adventurers

Weller immersed himself in Central’s international studies programs as deeply as the students, and glowed when hearing of the life-changing learning experiences they produced. He visited each of Central’s study abroad sites and helped forge especially strong connections between Central and Trinity University in Carmarthen, Wales. He had a special fondness for the Yucatán.

Lisa Rock ’87 interacted with him at both sites, first as a student in Wales and later in Mexico after moving to Mérida with the late Associate Professor Emeritus of Psychology Jim Schulze.

“All of these cherished and meaningful experiences connect back to Ken, who gave his support to the other major forces involved in building Central’s relationship with Yucatán, people like (former academic dean) Jim Graham, (faculty members) Harriet Heusinkveld ’39, Don Huffman, Larry Mills and so many more,” Rock says.

Travel with Weller didn’t involve shopping excursions and snapshots of the ocean. Sailing, windsurfing and scuba diving topped his agenda, along with wandering far from the standard tourist destinations to explore local villages. Even more pleasurable for he and Shirely was the 2,500-mile drive they twice made to Mérida in their Ford Explorer.

He was regarded as fondly by the program staff members and others he encountered in Mérida as he was at Central.

“The Wellers and Jim Graham and so on, the Yucatecans considered them part of the family,” Rock says. “They really valued that connection and I think it’s because of how Ken was just so humble and human in his interactions. And that makes all the difference.”

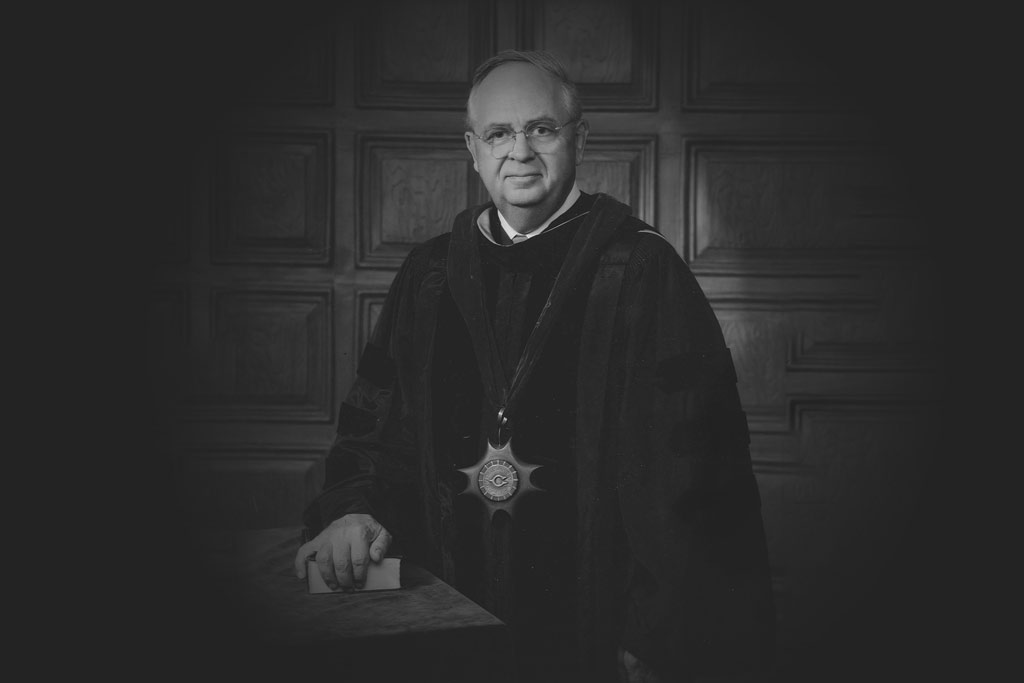

President Emeritus Ken Weller is joined by his wife, Shirely, at the NCAA headquarters in Indianapolis in 2013.

The Father of Division III

Weller’s outsized role in the development of the NCAA Division III and the integration of women’s athletics within the organization are well-chronicled.

Dan Dutcher was with the NCAA for nearly 35 years and eventually served as vice president of Division III. Weller’s kindness made an immediate impression.

“When he first met me, I was a young staff person,” Dutcher says. “He didn’t need to treat me special, but he was somebody that respected others.”

In his early years, the more Dutcher learned about Division III, the more he saw Weller’s name.

“What are its roots, legislatively, but, at least as important if not more, philosophically?” he asks. “All the roads went right to Ken. I call him the founding father of Division III.”

Dutcher says Weller was influential within Division III but adds “his fingerprints are all over” the creation of the NCAA’s overall structure as well.

Weller believed to his core that athletes who were diligent students became better athletes, and that students who were committed to developing as athletes became better students. He sought every opportunity to celebrate that.

When the Dutch were in Illinois for the 1988 softball championship, the team’s seniors had to miss Commencement ceremonies on campus. Weller arrived at the team’s hotel, in full academic regalia, to award the diplomas. He called it “bringing the mountain to Mohammed.” He didn’t want them to miss that experience and also relished the vivid illustration of combined athletics and academics achievement that the improvised ceremony represented.

Weller’s enthusiasm for co-curricular activities extended beyond the gym floor. He sang in the College-Community Chorus and church choir while encouraging students to participate in music, theatre and art activities as well.

“I do not want my legacy to be as a jock president,” he said. “I wanted to be an educator. To the extent that athletics can contribute to that, fine. But I want to be seen as the students’ friend, not the athletes’ friend.”

The Central Magic

Weller was convinced there was no place that does college the way Central does.

“I think there’s no doubt he really was in love with Central and the people associated with it,” Orr says.

Beyond its academic and co-curricular strengths, he sensed there was a certain kind of magic in the rural Iowa campus with the pond.

“I think what he meant by that is that Central had a sense of community that is pretty rare,” Miller says. “And he talked about community all the time. It was one of his themes. And by that he meant that we care for one another and work together. He had this whole spiel in speech after speech about how there was a division of labor in the college but that we were all working for the same goal. He did that more than any other faculty person or administrator that I know. And I think that repetition of the importance of community and caring for one another really did make a difference.”

It all served a single purpose, the learning process, which fascinated him. All other college activities were secondary to that mystical mind-bending moment shared by student and professor when the student first comprehends a concept. He would marvel over it every spring when he spoke at Commencement.

As the new graduates fidgeted in their robes, Weller would remind the audience that every job on campus, from admission counselor to academic dean to dining services director, existed for that classroom interaction. Weller’s hand would brush his face and he’d put a finger to his lips while pausing, as if pondering the thought for the first time. Then his finger gently pierced the still air of the steamy gymnasium as he proclaimed in a soft voice: “And that’s what it’s all about.”

President Emeritus Ken Weller leans his motorcycle against the fence while watching a softball game following his retirement.

We Made It Through, All Right

Still wearing a tie but sitting comfortably in his overstuffed chair at his downtown retirement residence above the Pella Molengracht, Weller’s mind drifted back once again to that troubled first year as Central’s president.

More than war protests were swirling as Weller prepared for a year-end trustees meeting. Under Weller’s predecessor, Don Lubbers, bold changes were implemented as the college opened its doors to constituencies beyond the Reformed Church. Some moves were met with controversy and rigid resistance. Even the new campus pond was mocked as “Lubbers’ Lagoon.” Tensions remained on a divided board of trustees and conflicts simmered. The meeting would require more delicate footwork than Weller ever displayed as a football lineman back at Hope.

“I had to go to that meeting, and it was very stressful in terms of how to handle other people,” Weller said.

Mercifully, the meeting ended. Weller wearily returned to Central Hall and slumped into his office chair.

“Finally, I called Shirely and I said, ‘Well, it’s over,’” Weller said.

Her response was immediate.

“Well, I didn’t like the job much anyway,” she said.

Weller chuckled loudly, both at the memory of her mistaken assumption and because of his love for Shirely and her direct manner that had kept him on track so often in their 71 years together.

Weller smiled.

“We made it through all right.”

Our Inheritance and Legacy

The Central College presidency is an inheritance and each of us in turn works for our successors.

The task set before us is to steward the fullness of the resources, creative energies and ambitions of the campus community to advance our mission, uphold our values, honor our history, embrace our traditions and pursue fresh innovations. We know and understand each other’s work set in the context of time given to us and the circumstances surrounding us. It is among the highest privileges each of us has enjoyed in our professional lives and profoundly meaningful as a personal journey. We see each other’s work through a unique lens of understanding only granted to those who have carried the responsibility.

Together we celebrate the life and legacy of our dear friend and colleague, Ken Weller.

Ken’s leadership of the college was marked by many enduring achievements that were informed by his predecessors and passed on to those of us who followed.

Notable among his many contributions is the broad institutional and national impact he had on the development of NCAA Division III philosophy, the original articulation of the “student-athlete” concept and the advancement of women’s intercollegiate athletics.

Above all, he was faithful to the essence of the college and yet challenged our academic community to evolve with changing times. His patient and effective service over a 20-year period yielded fundamental organizational strength that continues to serve as a sturdy foundation.

Through his time, Ken navigated the college through years in which our national discourse was strained by political unrest, international conflict and economic pressure, which invariably impact the academy. Yet he modeled for us the calling we each have as educators to generate light and not heat.

Ken has been a dear friend to each of us. By quietly giving and receiving counsel through the years, he was an active member of our community of Central College presidents. We feel this loss immensely, but we know that his hand in our shared work will always be present with us.

Well done, friend.

Don Lubbers

David Roe

Mark Putnam

To encourage serious, intellectual discourse on Civitas, please include your first and last name when commenting. Anonymous comments will be removed.

Randy Gunter

|

7:24 pm on July 27, 2022

Thanks for sharing this deeply personal reflection on President Weller and his legacy. As a newly minted African American freshman from Georgia, my arrival at Central in September 1970 was not without anxiety and questions about my selection of Central as my college home. However, one of my first encounters with campus leaders was with President Weller at his home as he welcomed new students. He was warm, curious about my experiences prior to arriving at Central and seemed genuine about my prospects for success. I recalled expressing some reluctance to him about finding my place so far away from my home. I will always remember his comments to me. He said, “You are here to learn. We can learn from you and I know you’ll learn from us as well.” That encounter stuck with me throughout my four years at Central and well into my academic experiences over the course of my career. I did get a chance to thank President Weller in person several years ago when I returned to campus for one of my class reunions. I am happy that I took up President Weller’s challenge ‘to learn and to teach’. President Weller’s Legacy lives on…

Randy Gunter, Ph, D. Central College, C/0 1974