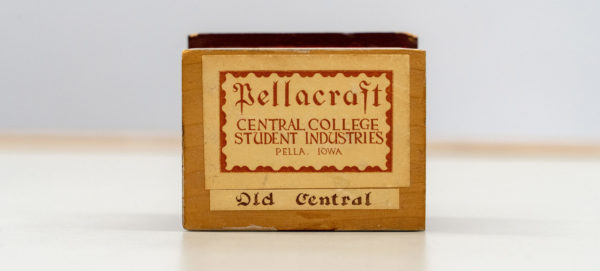

A model of Old Central Hall made by Central Industries shares a tabletop with a photo of student workers posing with cultivators made by the Industries.

Nearly three decades before the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 created federal work study programs, Central College built its own.

Initially called the Earn-Your-Way Corporation and later Central College Student Industries (Central Industries for short), the innovative program helped hundreds of Central students pay for their educations during the depth of the Great Depression.

THE BAD OLD DAYS

Unemployment topped 20% nationally in 1935. Central, then 82 years old, enjoyed an excellent academic reputation and no shortage of interested students. But many didn’t have tuition money or any way to earn it. Would-be college students seemed locked out of higher education; some already enrolled risked dropping out. The college faced a declining enrollment it could ill afford.

Most colleges hunkered down during the depression. They reduced payroll by attrition and more than 80% of institutions surveyed cut faculty salaries, often while increasing workload. They cut campus construction projects by nearly 90%. Some elite colleges with wealthy students raised tuition to make up for lost revenue from their endowments, according to “Depression, Recovery, and Higher Education,” a report published in 1937 by a special committee of the American Association of University Professors and cited in “The Bad Old Days: How Higher Education Fared During the Great Depression.”

A BOLD VISION

Ben Hoeksema leans on a bandsaw while

addressing student workers. An experienced

Pella woodworker and cabinetmaker, he served

as manager of Central Industries.

Central wasn’t most colleges. Unwilling to lower the quality or accessibility of its education, it developed a plan that involved three new hires, renovating its most iconic building and making a Central education affordable to students with financial need.

At a spring meeting, “the much-discussed proposal for an ‘earn-your-way’ corporation was brought before the board [of trustees] with much enthusiasm, and a committee was formed to report to the board in June,” announced The Central Ray in a March 22, 1935, article. [All quotes to follow also are from The Central Ray.]

By May 10 of that year, the college proclaimed it was “entering upon a new plan of giving aid to worthy needy students” by creating a factory staffed by college students. The college promised that if a student was “efficient and cooperative,” they’d be able to earn a large portion of their college expense. Students could even work year-round — enough to allow them to earn sufficient funds to maintain a full course load and graduate with their class.

PROFESSIONAL IMPLEMENTATION

The college didn’t mess around. It hired Simon Heemstra (sometimes spelled Hiemstra), a manufacturing executive formerly with Standard Oil Company, General Motors and National Biscuit Company. He was given the title professor and the mandate to start a factory to make high-demand products with as little capital as possible.

Heemstra in turn hired George Heeren, a former industrial foreman. The two came up with something they called Buildertoy: A kit of parts from which children could assemble “a complete living room, bedroom and dining room suite, all contained in a neat box” along with a tube of glue.

The college took over the old Two Van Shoe store in downtown Pella for a workspace. Heemstra and Heeren designed and built some woodworking machines, devised an assembly line and started putting students to work sawing, sanding and packaging kits. The kits were sold in stores in Pella so as not to undercut local businesses. Heemstra went on the road and secured wholesale orders from chain department stores such as the S.S. Kresge Company, one of the 20th-century’s largest discount retailers, later renamed Kmart Corporation.

STARTING ON A DIME

Buildertoy retailed for 10 cents. Heemstra and Heeren figured that way, any parent could afford to buy one for their children for Christmas. They were right. Soon shifts of Central students were working “from 10 to 12 in the morning, all afternoon and sometimes into the evening” to keep up with orders. The raw materials were so cheap and the assembly line so efficient that even at a dime a kit the product made money.

Central Industries quickly followed up with a farm set with “a hog house, chicken house, granary, etc., with a large amount of fence and posts, uniquely designed, so that the child can build his own fence around the farmyard.” It, too, was a mass-market hit.

Central students assemble and pack thousands of church-shaped banks. They were sold to congregations and used to take up special collections.

A CLASSIC SUCCESS STORY

From there, Central Industries took off.

Art Professor Vernon Bobbitt became another mainstay, helping design products and overseeing manufacturing. Ben Hoeksema, an experienced Pella woodworker and cabinetmaker, eventually joined as manager.

Central Industries kept coming up with new products, including:

- Church-shaped wooden banks sold to congregations for use in fundraising.

- Folding ironing boards for the Rite-Hite Ironing Company of Des Moines, Iowa.

- Laundry baskets to go with the above.

- Wooden footstools of varnished and waxed wood with woven rush tops.

- Folding wooden banquet tables.

- Garden tools, including a wholesale order of 7,000 hoes for the Garden City Cultivator Company of Pella, Iowa.

- Spark Arrestors for chimney tops to prevent sparks from setting roof fires, for the Grinnell Mutual Reinsurance Company of Grinnell, Iowa.

The business outgrew one facility, then another. Over time, the factory and offices hopscotched all over Pella’s downtown. In addition to the Two Van Shoe store, they filled the buildings formerly occupied by the Woodrow Washing Machine Factory, the Feeder Works, the Garden City Overall Factory and the Vos Implement Company.

The shop floor. Central Industries’ rapid expansion caused it to occupy five buildings in as many years.

Students become not only workers but foremen, accountants, managers and board members, learning business skills that supplemented their courses. A 15-member student board — eight elected by Central Industries student workers and seven appointed by management — elected its own officers and met twice per month. By fall semester 1937, Central Industries employed 85 students — a significant portion of the college’s student body at the time.

In 1938, in addition to producing products for branding and sale by others, Central Industries introduced its own Pellacraft brand. The biggest seller was the industries’ folding banquet tables sold to churches, schools and lodges. The industries made up to 50 tables monthly and “found it impossible to keep production ahead of orders” because of demand.

In 1940, 90 students worked at the plant during the academic year; 15 over summer break.

During the late 1930s Central Industries also:

- Renovated Jordan Hall.

- Made “much of the furniture for the college,” including tables, chairs, dressers, desks and more.

- Imported and distributed tulip bulbs from Holland. (“Bulbs may be ordered at any time and will be shipped to any point.”)

- Acted as a job shop equipped to do “all types of woodwork” and “most types of metalwork, besides having some skillful sign painters.”

Archival photographs of Central students with graduation dates as late as 1951 indicate the industries likely continued through at least the mid-1940s.

Later, the industries branched out into making larger products, including furniture, some of which was used in residence halls and classrooms. Norman Den Hartog ’51 of Knoxville, Iowa, stains an end table; Bill Baird ’50 of Johnstown, New York, finishes a bookshelf; and Tom Carlson ’50 of Chicago, Illinois, assembles a table with a brace and bit.

A TIMELY SOLUTION

Central Industries boomed during an economic bust. It created needed products of high quality at reasonable prices. It helped Central improve its buildings and furnishings when other institutions were deferring maintenance. It trained students in useful trades and crafts and in the operation and management of a sizable business. Most important, all its profits went to pay the college expenses of its student workers.

Central Industries, noted The Central Ray in May 1938, “is helping to solve one of the major problems for college men and women — finances. Every student who will cooperate … will not only make a great success of Central College Student Industries but will also train … in some valuable experiences which will make … life more pleasant, richer and more sympathetic with … fellow workers, not only in college, but also out in the wide, wide world.”

Experiential learning, internships, work study and co-op programs are popular now, and for good reason. But we know of no other small liberal arts college that bootstrapped an entrepreneurial manufacturing industry during a financial crisis solely for the benefit of its students — and succeeded at such scale.

After Pellacraft branding was introduced, many Central Industries products were identified by this label printed by a hand-carved block.

To encourage serious, intellectual discourse on Civitas, please include your first and last name when commenting. Anonymous comments will be removed.

Comments are closed.