In the early 1940s, nearly every man on Central College’s campus was studying to be a pilot.

That took some doing. Pella, Iowa, didn’t even have an airport in 1940. And Central was a liberal arts college with an otherwise almost entirely female student body (most male students were off to war). But the armed services needed more pilots than the military could train. According to The Central Ray, Central President Irwin Lubbers “offered the services of the college to the government in a trip to Washington and was assured that Central would be one of the first small colleges considered in any war time education plan.”

The government was good to its word. Central launched a flight training school virtually overnight.

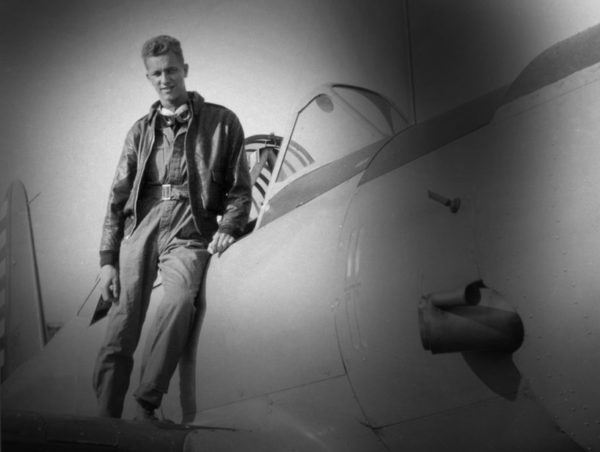

A rare color photograph of Paul Metcalf, flight instructor, ready for takeoff.

NO EASY COURSE

As part of the federal government’s Civilian Pilot Training program — later called the War Training Service — Central offered four, eight-week courses of 240 hours of study each. Students were paid a stipend of $100 per month — “scant enough to keep one in board and room and shoe polish,” according to a Sept. 4, 1942, article in The Central Ray.

CPT was no easy course: Even the so-called “Elementary Ground School” consisted of:

- 20 hours of Physics

26 hours of Math

26 hours of Math- 16 hours of Civil Air Regulations

- 10 hours of General Science of Aircraft

- 36 hours of Navigation

- 22 hours of Code

- 58 hours of Military and Physical Training

- 12 hours of Military Science and Discipline

- 24 hours of Meteorology

- 12 hours of Aircraft Identification and

- 35 hours of flying from the hastily constructed Pella airport

The secondary school taught more of the same, plus Theory of Flight and Aircraft and Aircraft Engine Operation.

“Students begin flying at sunup and at 8 o’clock they begin the ground school day. The afternoons are spent in flying, evenings in classes and study. Saturday mornings are kept for inspections and flight. … Central’s school of the air has so far drawn only unqualified praise from the inspectors,” reported The Central Ray. The program had its own bus to shuttle students from campus to the airport five times daily. At the program’s height, training aircraft burned 6,000 gallons of aviation gas per month.

Cadets get ground instruction from Earl Pohlmann at the Pella airport.

FROM LATIN TO AIRCRAFT CONSTRUCTION

At first, classes were held in various buildings in downtown Pella and students were civilians. Later, classes met in Jordan Hall and students were Army or Navy cadets (the U.S. Air Force wasn’t established until 1947). Military instructors taught flying, while Central faculty taught ground school classes.

Tunis Prins, director of athletics and professor of physical education, coordinated the program. Henry Pietenpol, academic dean and professor of mathematics and physics, taught the cadets physics. Gerrit Vander Lugt, professor of mathematics and later president of the college, taught math and navigation. Long-time Professor of Latin and Greek Herbert Mentink taught Theory of Flight and Construction of Aircraft. Laura Nanes, beloved professor of history, taught meteorology. Ray Doorenbos ’56 taught mechanics.

Apparently, the faculty made the disciplinary leaps well. According to the military, 40% of cadets washed out of military flight training programs; less than 5% of CPT-trained pilots did. They went on to fly everything from ferry planes to combat planes.

The pilot training program literally took over Graham Hall, transforming it from a women’s residence hall to a barracks.

MILITARY TAKEOVER

Life for Central’s female student body changed dramatically, too. They were kicked out of Graham Hall as the “women’s dorm” was converted — in three days flat — to a barracks.

“Giggles, howls of ‘Who’s got the iron?’ and the swish of formals were replaced by butch haircuts, navigation cases and the purr of electric razors,” wrote Carol Hubrex ’46 in a June 2, 1944, article in The Central Ray. The women were moved to “five attractive cottages” surrounding campus.

BACK TO NORMAL

Jake DeHaan and Bob Nemmers getting

ready to fly.

By June 1944, the military had ramped up its own pilot training and the War Training Service no longer was needed. Central faculty went back to teaching their liberal arts curriculum; women moved back into Graham; and Central waved goodbye to the aviators — apparently with good feelings all around.

“Central College has given to Cadet Flight Training much more than the courses offer. It has furnished the cadets with a Christian atmosphere and a cultural environment. It has been in every respect a college as well as a training ground. Students at Central, whether in military service or in the regular college training, are to be congratulated,” wrote Lt. James S. Duncan, the resident naval officer, upon his departure.

Hubrex put it more simply. “Really,” she wrote, “it’s been fun having the cadets on campus.”

Lt. Robert G. Menning ’42 was copiloting a B25 C bomber such as this when he was shot down in

the mountains of North Africa. Credit: United States Air Force

POW ISN’T AS BAD AS IT SOUNDS

Lt. Robert G. Menning ’42 was shot down in combat. He was listed as missing in action on Jan. 22, 1943, and feared dead.

But eight days later, his family got a letter from him. “I am well and safe and will be home as soon as the war is over,” he wrote — to the huge relief of his wife, Lolly Menning ’42.

He miraculously survived and was taken prisoner by the Germans.

His letter was published in its entirety in The Central Ray April 2, 1943. It is a model of nonchalance and reassurance:

“I am now a prisoner of war, but please don’t worry about me because a prisoner of war isn’t as bad as it sounds or as you think,” he began.

“I was shot down in the mountains of Africa. I was the only one who got out alive. I bailed out at 200 feet. It was by the providence of God that I was saved.

“The Germans treat us very good. Good food, sports, movies, candy, cigarettes, etc., mostly from the Red Cross. … The officers live together. We even have colonels and majors here, three colonels from Iowa. … We all have one consolation as prisoners and that is that we will be alive after the war. The first thing they do after the war is that they exchange prisoners. … Don’t worry about me and tell everyone to write.”

Lovingly, Bob

True to his letter, he returned home alive and well after the war’s end.

“LOVE [AND LOSS] VIA BOMBER”

Perhaps the most heartbreaking story of the era concerns Lt.Walter J. McCain ’42 and Martha Childress Miller ’44. McCain, a Central student from Closter, New Jersey, enlisted in the Army Air Corps after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. He joined the first Civilian Pilot Training course offered at Central. Somehow, he and Childress managed to find time to fall in love during McCain’s pilot training in spite of the dawn-to-dark cadet regimen.

Lt. Walter J. McCain ’42 was killed when the bomber he was piloting was attacked, caught fire and crashed in Germany.

McCain entered the Army Air Corps service soon after the completion of his pilot training during his second year at Central, forcing him to leave Childress behind. But when he found he’d be flying his B-17 E Flying Fortress Heavy Bomber right over Pella on a flight from Topeka, Kansas, he wired her the approximate time. According to a Nov. 13, 1942, article in The Central Ray titled “Love Via Bomber,” Childress stood in front of Graham Hall in the cold and dark for over an hour just to hear the plane’s engines as he passed overhead.

Maybe she had a premonition, because days later she left Central for a week to visit McCain in Topeka. They were married just 18 days before he was deployed. Childress was still a student.

On April 19, 1944, the B-17 McCain co-piloted was hit by anti-aircraft fire over Germany and caught fire. McCain and his fellow pilot managed to keep the bomber in the air long enough for the other eight men in the crew to bail out. But the pilots went down with the plane and were killed. The surviving crew members were taken prisoners. All came to pay their respects to McCain’s family after the war for his heroism in helping ensure their survival. McCain is buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

MORE VINTAGE PHOTOS!

Unless otherwise indicated, the photos illustrating this article are from the Florence E. Meredith Lilly collection in the Central College Archives. View these and other photos from this collection at central.edu/lilly-collection.

The fleet of training aircraft and the number of cadets had grown significantly by the time the program ended in 1944. This photo shows only half the cadets and one-third of the aircraft present at the program’s height.

Flight instructor Paul Metcalf poses with an early flight simulator — called a Link trainer — used in Central’s ground school instruction.

Navy cadets in a classroom with Marvin Baker, instructor.

To encourage serious, intellectual discourse on Civitas, please include your first and last name when commenting. Anonymous comments will be removed.

Comments are closed.